The probability yardstick

This post is an attempt to explain probability – to others, and maybe also to myself. Readers will judge how far I've come.

Let's start with the probability of a future event.

An event is the outcome derived from the observation of a variable. The probability of a future event is the amount of plausibility we assign to it, expressed as a real number between 0 and 1. Depending on what we are looking at, the event in question might be something that either happens or not, or it might be one out of multiple possible outcomes.

Consider the following questions:

- Will it rain tomorrow?

- How many days will it rain next month?

- How much total rain will we have next month?

Given that we are unable to predict the future with absolute certainty, realistic answers to the questions above are as follows:

- A number X (plus the implicit counterpart 1-X)

- A series of numbers X1…. Xn, where n is the number of days of the month

- A function that assigns a number to each possible amount of rain, from 0 to infinity

The calculations that answer our questions express plausibility in a binary, categorical, or continuous result space respectively. And they must sum to 1, by definition. Or to 100, if you prefer percentages.

Plausibility – the degree of belief we associate with a particular outcome derived from observation – should be regarded as a primitive concept, just like mass, length, and time are primitive concepts in Newtonian mechanics. We understand mass, length, and time, but within the theory they can't be explained any further; the theory only tells us how to measure them.

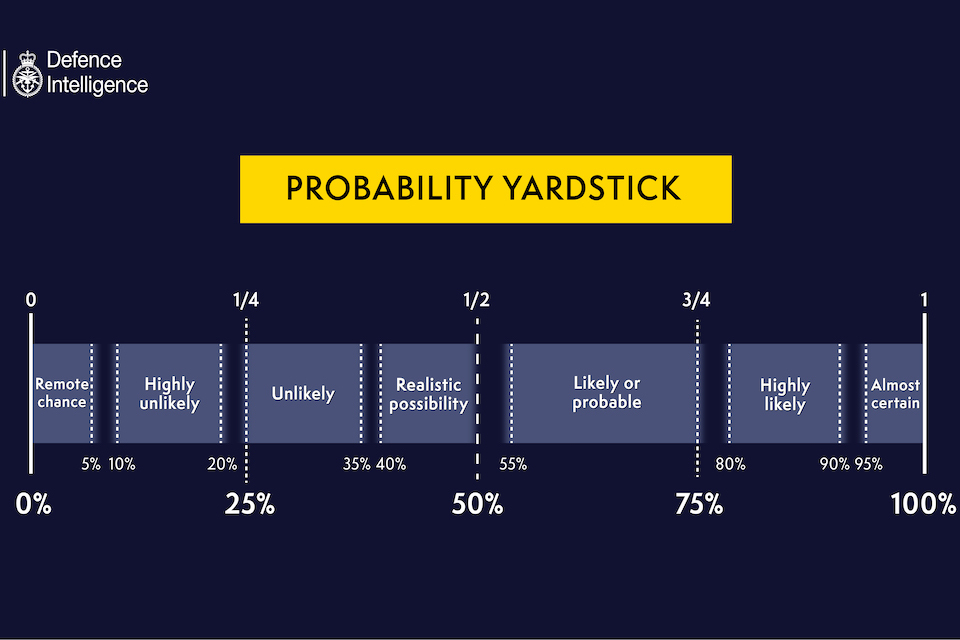

The equivalence of probability and plausibility is illustrated in a straightforward manner if we resort to the probability yardstick created by the UK's Ministry of Defense:

If probability is simply defined as plausibility, then probability is also a primitive concept rather than a derived quantity. This means that we need a process to measure it, but we can't explain it any further — our intuition must complete the picture and connect it to the terminology we naturally use, as seen in the image above.

The elephant has just left the room.

So the question now becomes: how can we measure probability?

My understanding is that the following probability assignment methods are available:

- previously measured frequencies

- physical / mechanistic model

- Maximum Entropy Principle, using whatever information is available

- ad-hoc reasoning

Choosing the right process is not always simple, and every choice comes with assumptions.

Previously measured frequencies are useful for situations where an observation can be repeated many times, under the assumption that the observed phenomenon does not change over the course of time. For instance, assuming that the Laws of Physics won't change, we may want to accept that previously measured frequencies related to coin flipping (or dice rolling) won't change and accept them as probabilities. Same goes for roulettes, slot machines and similar mechanical devices.

But our daily challenges are not always related to gambling...

If we want to know how many rainy days we'll have next month, we can build a probability distribution from the frequency of each possible number of days recorded in previous years. We would need to assume that weather data had been accurately collected and that climate does not change – or at least not fast enough to invalidate the use of past frequencies as future probabilities.

But what would we do if historical data failed to include daily information?

Let’s suppose that, for the previous 50 year period, only the average number of rainy days for each month was recorded. Let’s call that number N for our particular month. In this case we would apply the Maximum Entropy Principle in order to look for a probability distribution with prescribed average N and domain [0, M], where M is the number of days in the month. We would find the Binomial distribution of parameter p = N / M. This would be worse than the distribution obtained from daily data, but still much better than to assume all possible values are equally likely to happen.

Now, if we want to know whether it will rain tomorrow, no reasonable combination of historical data and climate stability will help. We know that it's more likely to rain in some months than in others, but we don’t know from climate history the specific days in which we'll have rain. For this case we need a physical model – specifically a weather forecast model. Weather forecast models have become very accurate in the last couple of years and can predict what happens tomorrow based on what happened in the previous days.

Probability assignment becomes harder as information becomes scarcer. In our previous examples, repeatability enabled a history of frequencies which, under reasonable assumptions, could become probabilities. Since repetition is at the core of industrial processes, many such cases could be found. The flight of airplanes, for example, is made possible by repeatability combined with a deliberate effort to minimize the probability of failure.

On the other hand, many cases provide a single occurrence of the variable: once it happens, the system changes and the event can't be observed again under the same conditions. Question: will my company increase its profits by at least 7% next year?

This is tricky. A company’s profit does not have historical data that can be reused under reasonable assumptions of stability. Furthermore, a physical/mechanistic model that relates one particular company with the entire economy might be too complex to be reliable. We are then left with ad-hoc considerations for estimating revenue and cost scenarios, and with assigning a probability to each combination of scenarios we come up with.

This difficulty is found in many other cases: Is this customer going to churn? Will this lead convert into a sale? Will the IT systems of my company be hacked? Will my team win the championship this year? Whenever the situation we observe is a unique occurrence, we are stuck in ad-hoc land.

Take away message

Probability can be understood by intuition.

But even though we have a yardstick that connects probability to our intuition, there is no probability assignment method that suits every case. Non-repeatable observations are particularly concerning because there is no way to assess and improve assignment processes – the underlying reality changes over the course of time.

Whenever we need to assign probabilities, we should review the available processes and choose carefully which one to use. If we are uncomfortable with communicated probabilities, we should ask what assignment process has been used.

Notes:

-

Obtaining the Binomial distribution from the Maximum Entropy Principle is not completely straightforward. I will provide details in a separate post.

-

The examples of churn detection and lead conversion were not random. For large numbers of customers or leads, the unique character of each situation starts to erode and machine learning algorithms can be used to automate similarity detection, segmentation, and probability assignment. This will be the subject of another post.